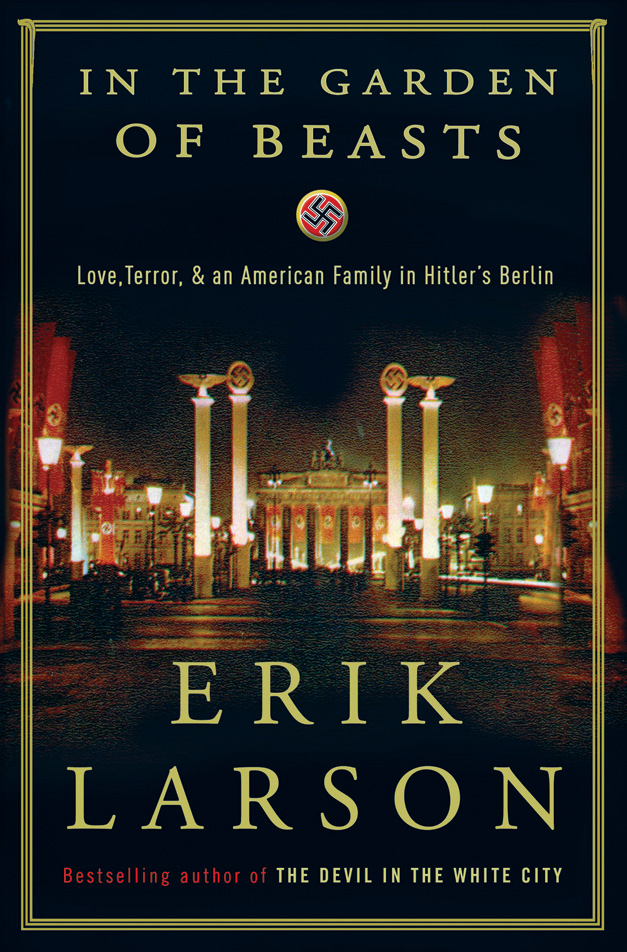

First, I should mention that I really like Erik Larson. Of course I enjoyed Devil in the White City, and I thought Thunderstruck was much better than people gave it credit for. But I am also a huge fan of his first book about the creation of the National Weather Service, Isaac's Storm.

What I enjoy most about Larson's narrative nonfiction is how he takes lesser known moments in history and pairs them with larger ones. So a killer is paired with the World's Fair (Devil), the invention of transatlantic radio communication with another murderer it was used to catch (Thunderstruck), and the creation of the National Weather Service with a devastating hurricane (Issac's). Larson gives us a known frame of reference, lulling us into a comfort zone, and then throws us a huge curve ball, knocking you off your feet and screaming at you to pay attention to the history (although it feels more like a story) he is telling you.

It is a brilliant method and frame which Larson has perfected. Although it is this perfection which is what is keeping this book off my 2011 Best List. This book was wonderful and deserves all of the accolades it is getting, but I expected that. Larson delivered on my expectations; therefore, when I sat down and looked back on my "best" reading experiences of 2011, this one does not stand as exceptional precisely because it was so good.

So that's my mini lecture on Larson. Here's the info on this book specifically.

Here the larger, known frame is Hitler's improbable rise to power seen through the eyes of the most unlikely diplomat, William Dodd and his daughter Martha. Dodd was a historian who wanted to change the diplomat culture. He was a true believer in Democracy and was mad that you had to be independently wealthy to be an Ambassador. He managed to get the Berlin post in the early 1930s, a post FDR was having trouble giving away, and spent the early years leading up to WWII railing against the tradition of wealth in the diplomat core and sending dire warnings of Hitler back to America. Unfortunately, both arguments were dismissed as frivolous.

Dodd's daughter Martha was also quite a character. A divorcee playgirl, she dated many key figures in Hitler's government, many of his enemies, and even once went on a date with Hitler himself. But she found her true love in a Soviet spy named Boris. Her story is one of the accidental spy. And, one of the most interesting parts of this story is Martha's transformation from one who thought that Hitler would bring good things to Germany to absolute disgust for the man and his followers.

Larson's book is about the Dodds and about the early years when Hitler was solidifying his power base. The Dodd's bore witness to many atrocities leading up to the war. They did not ever see a concentration camp, but they saw the torture of Jews and were there for a Hitler ordered mass purge of his enemies. They returned to America before Hitler began his European campaign of aggression, but they left knowing a horrible war was coming. And even worse, they knew they tried to warn the world of the problem and no one would listen.

Everything I said about Larson's appeal before this short summary applies here. He uses letters and official documents to tell his story, quoting extensively from William and Martha's correspondences. You really get a bird's eye view of the years leading up to WWII. It is alternately enlightening and upsetting to see how easily Hitler could have been tripped up along the way.

Larson's use of primary documents allows the reader to feel as if he or she is there, in Berlin, during the early 1930s, living amidst the terror and fear.

Martha especially is quite a character. She is a wanna be spy and sex crazed playgirl. She goes through men like most women of her time went through new outfits. She took a lot of heat for her behavior, but she was quite an independent spirit.

Read this book if you like Larson, but even if you haven't enjoyed his work in the past, read this book if you think you have read everything on WWII already. Larson managed to find a unique and enlightening angle to a time period that can be overdone by both historians and novelists.

On a final note, I listened to this book and really liked the narration. It was engaging and even toned. I found myself wanting to return to the story for both the way it was written and the man telling it to me.

Three Words That Describe This Book: fresh look at history, enlightening, engrossing

Readalikes: Of course there are hundreds of good nonfiction WWII options, but a few that appeal specifically here are:

- Democrat and Diplomat: The Life of William E. Dodd by Robert Dallek

- Resisting Hitler: Mildred Harnack and the Red Orchestra by Shareen Blair Brysac

- The Coming of the Third Reich by Richard J. Evans

NoveList also pointed me to a fascinating novel, Every Man Dies Alone by Henry Fallada. From the PW starred review:

/* Starred Review */ This disturbing novel, written in 24 days by a German writer who died in 1947, is inspired by the true story of Otto and Elise Hampel, who scattered postcards advocating civil disobedience throughout war-time Nazi-controlled Berlin. Their fictional counterparts, Otto and Anna Quangel, distribute cards during the war bearing antifascist exhortations and daydream that their work is being passed from person to person, stirring rebellion, but, in fact, almost every card is immediately turned over to authorities. Fallada aptly depicts the paralyzing fear that dominated Hitler's Germany, when decisions that previously would have seemed insignificant—whether to utter a complaint or mourn one's deceased child publicly—can lead to torture and death at the hands of the Gestapo. From the Quangels to a postal worker who quits the Nazi party when she learns that her son committed atrocities and a prison chaplain who smuggles messages to inmates, resistance is measured in subtle but dangerous individual stands. This isn't a novel about bold cells of defiant guerrillas but about a world in which heroism is defined as personal refusal to be corrupted. (Mar.) --Staff (Reviewed January 12, 2009) (Publishers Weekly, vol 256, issue 2, p29)Jeffrey Deaver has a thriller entitled, Garden of Beasts: A Novel of Berlin 1936 which I think is a good option, especially for fans of Martha's accidental spy part of the story. Another review also said her escapades had shades of a John Le Carre novel.

Thinking outside of the WWII box here, for another book which takes a well trod history and gives it an enlightening and surprising new spin, try The Known World by Edward P. Jones.

One more review before my best of the year post.

The story is told in a realistic and very readable form. I had a little trouble getting started with it due to recent cataract surgery, but once I picked it back up, I almost couldn't put it down to go to sleep, or go to work or anything. I read the last 330 pages of it in two evenings straight.

ReplyDeleteEric Larson is a wonderful writer, who backs up his story with solid research. Kudos to him!

I immediately began reading his book "Thunderstruck" as soon as I finished "In the Garden of Beasts". It will also be an excellent read.